Throughout the week, as we watch another war unfold, our anxiety about peace in the Middle East and around the world comes to a slow boil. We know from science that a frog will sit in water that is slowly heating up without jumping out of the pan because they don’t notice the small increments of temperature change, but we don’t have to do that. We can move out of our frying pan of funk, take a few deep breaths and notice that the sky is still blue.

Breaths. Breeeeeethes. Or breathings? What is the plural of more than one breath, anyway? Just saying it that makes me want to do more of them. I don’t need to wear a colorful wrist band to remind me that my higher calling could simply be to calm down and take a breath. As my grandmother us to say when things got over-heated: “Let’s not make a federal case out of this!” and after living through five wars, she had mastered the art of breathing easy.

A couple of weeks back, a longtime friend of mine returned home to visit, and we also had a chance to take a breath and catch up on all the news that’s fit to print. The speed and intensity of our conversation would rival one of those commercial you hear where a professional fast talker says every word on an allergy medication bottle in five seconds, except that our conversation lasted into the wee hours of the morning. My friend, Woody, has lived in Switzerland for most of his adult life, landing there partly from his propensity for language but also because of a spirited love for travel and adventure. We were best buddies in school but bonded through a life-changing adventure trip out west, where we battled through our coming-of-age hardships. The mountaineering school we signed up for took us into country that was both dangerously rough and breathtakingly gorgeous, shaking us to the bone and echoing through our personal landscapes long after the trip had ended.

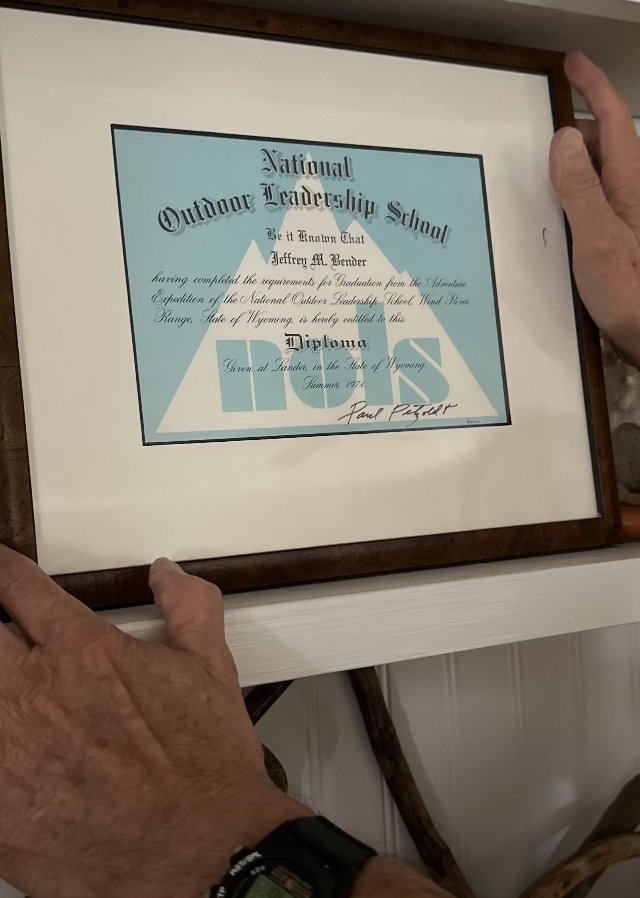

Back in the day when we thought we had the world by its tail, we found a small ad in a magazine for a wilderness school in Lander, Wyoming. Within a couple of weeks, and with a lot of begging and pressure on our respective parents, Woody and I were enrolled in a blandly described “Adventure Course” in the Wind River Range, an area Hemingway himself described as “damn lovely country,” second, he said, only to Africa in its beauty. His endorsement seemed to be enough for our parents to sign the checks and waivers to National Outdoor Leadership School, described in the small print as a survival school. We sold them on the idea that our education would be expanded by leaps and bounds, not knowing of course that many of those leaps would be made above 13,000 feet.

Let me pause at this point to say that it is only through the grace of God that I was saved from my own brand of dull-witted decisions in the wilds of Wyoming, and I would add that during my two-month course in the mountains, there was never a time that I didn’t expect to chop off my own hand with an axe or be trampled under the hooves of a mule deer.

That fear would begin at the outset with the plane ride out to Lander, Wyoming. The airline, still in existence today, lived up to its Frontier name, a label that describes the most primitive kind of plane, one designed in the Renaissance and powered by a wind-up rubber band that uncoiled within the first few minutes after take-off. If opportunity is the mother of invention, then this ride gave us the opportunity of a lifetime – to glide over the Grand Canyon uninhibited by the sound of the any working motor and ride solely on the thermals like an eagle. As our airplane sputtered down into Lander International, I had a feeling that my life, once reflective and shiny like a sheet of tinfoil, was about to be unveiled before me as a wrinkled mess.

At NOLS headquarters, we began organizing everything we needed to begin our journey, crowding everything from sleeping to cooking gear into what soon became a sixty-pound pack. When our instructor came along and dumped it all out on the ground and told us to start over, we got the message. Toothpaste went to the wayside for baking soda. Extra underwear was needless when one pair could be washed in a mountain stream. Item by item, we whittled down our loads and learned that to travel wise was to travel light. It was lesson in both humility and how to live simply, but also a reminder that a mountain tolerates dirty underwear a lot more than dead weight in a backpack.

Even when I make a purchase to this day, the voice of Skip Shoutis, my wilderness instructor, still rings through: Do you really need this? Do you have something like it already that will do the same thing? I haven’t always lived up to that notion of frugal and spartan living, but being forced to dump the extras redirected my vision towards the stunning scenery – white studded peaks of snow and rolling glacier valleys – a hallmark postcard view everywhere I looked. What mattered so much didn’t matter with views like that, and I forgot about all worldly events like Vida Blue’s fastball in the World Series or the Watergate debacle back home. As Woody and I would agree many years later, those lessons we learned at NOLS right out of the gate brought about a paradigm shift in our spoiled middle-class lives.

The first five-mile hike on day one seemed easy enough until the trail turned into a balancing act across three miles of solid boulder fields. At the end of the day, eating my burnt baked potato before falling exhausted into my sleeping bag, I neglected a cardinal NOLS rule, a policy of LEAVE NO TRACE, and left my tin foil in an open fire pit. On the second day, after negotiating a five-hundred-foot cliff and arriving at our next site, I was met by my instructor who handed me the torn other half of my tinfoil and told me to hike back to the previous site, retrieve the other half and then catch up to my hiking group by the end of the day.

When I stumbled into the new camp the next day nearing what I thought was my own certain death, the instructor held his piece of foil up to match my retrieved piece. Only then was I allowed to pitch camp with the others, get something to eat and go to bed knowing that taking care of the Wind Rivers was gospel at NOLS. That’s the kind of gospel that would be part of me forever. I’m convinced our best lessons are learned through difficulty, the lessons to travel light, pick up after ourselves, and enjoy the scenery around us as we go. We are a miserable lot, we humans, but we learn best not through our wins and victories but though the torn pieces of foil we leave at the bottom of the mountain, the ones that eventually find their mate at the top again.

A few short years later, I signed up for a canoe-for-credit college course in the Adirondacks, a two-week class in biology, geology and ecology all rolled up in a sleeping bag. A week in, I failed at another die hard NOLS rule, the one about always boiling my eating utensil after every meal and ended up with a bad case of the trots, which hit me like a vengeance about half-way up a mountain. Feverish, dehydrated and not thinking straight, it was another fellow hiker, a young man who also had been through NOLS training in Wyoming, who herded me back to camp along a precarious ten-mile trail. He did it alone, without help, because he had pounded the trails out in the Wind Rivers like me, knew how the outdoors worked, and understood the serious business of survival. Lucky for me, because I wouldn’t have made it without his skill set marching relentlessly in front of me.

Before my friend Woody left that night from our home, long after we both had dissected our collective experiences in the Wind River Range, we sat reveling and in wonder over how we ever survived such a grueling wilderness experience.

“Woody,” I began, “I’ve been meaning to ask you this for a long time, but were you ever scared when you were out in the Wind Rivers?” “Only every day!” he blurted.

And yet, we both managed, as two scared spitless boys in the middle of nowhere, to step out of our tents every morning, breeeeeath in some still mountain air and look up at a pristine sky that was as vast and blue as the day before.